In a diminutive wooden house tucked behind the tile-topped white walls surrounding Tenryuji Temple, a World Heritage site in Kyoto's Arashiyama district, lives Henry "Seisen" Mittwer, 91, a Japanese-American Buddhist priest, author, ikebana and ceramic artist.

|

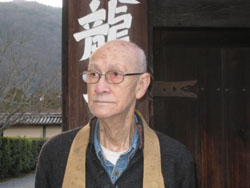

| Buddhist priest Henry Mittwer in front of the Tenryuji Temple in Kyoto's Arashiyama district. JANE SINGER PHOTO |

On a recent midwinter afternoon, as unseen tourists streamed by meters away, Mittwer, with his wife, Sachiko, 89, sat and reflected on a life that, Zelig-like, entangled him in many of the most wrenching events of the 20th century.

Henry Mittwer was born in Yokohama in 1918. His father was an American film distributor who first came to Japan in 1898 as a seaman en route to the Spanish-American War being waged in the Philippines. His mother was a former geisha from the geisha quarters in Tokyo's Shinbashi. He was the youngest of three boys.

An early but formative experience was the Great Kanto Earthquake in 1923, which killed more than 30,000 in Yokohama alone. Mittwer, then 5, remembers grasping his mother in terror as they ran from a house that was convulsing around them. The family had to camp out in their yard for several days before their house was again fit for habitation.

A photograph from that time shows Mittwer beside his mother, flanked by his two brothers and two neighbors, who are all armed with spears and rifles. "We had heard rumors at that time that Korean residents had dumped poison in the water supply and feared that they would revolt," he explained.

In fact, many Korean residents of Yokohama were reportedly lynched amid the suspicions enflamed after the temblor. This was perhaps an early harbinger that intercultural relations would not always go smoothly.

After the quake, Henry and his family spent 2 1/2 years living in Shanghai, but in 1926 the family returned to Yokohama. Henry entered St. Joseph's College, a Jesuit-run international school. "At school I spoke English, at home I spoke Japanese, but I never had a sense of being different. Yokohama was a very cosmopolitan place at the time, with all kinds of people ? Indians, Chinese, people of mixed nationalities. I wasn't stared at or treated differently," he said.

When Mittwer was only 9, his father returned to the United States for good, along with an older brother. "Father sent us checks for awhile to cover school fees and expenses, but he lost all his savings in the stock market crash of 1929. After that we moved around, from one house to an ever smaller one, as the checks stopped coming," he said. Finally, when Henry was 16, he was forced to leave school and look for work.

After many years he decided to travel to the U.S. in search of his father. "I wondered what he was thinking about us, so I took all my savings and bought a second-class ticket on the Hikawa Maru ocean liner to Seattle." That ship is now a floating museum berthed in Yokohama harbor.

Mittwer was eventually reunited with his brother and his now frail and defeated father in Los Angeles. The year was 1940.

A year later, in December 1941, Mittwer found himself trapped by the amplifying effects of the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor. The Japanese-run store where Mittwer had worked was soon forced to close, so he looked for other work. "But because I wrote 'Born in Japan' on job applications, no one would hire me. Without a job or a place to live I finally had no choice but to enter an internment camp," he said.

From 1942 Mittwer lived in five of the 10 internment camps the U.S. War Relocation Authority had thrown up in scarcely inhabited areas of the western U.S. for nearly 120,000 Japanese and Japanese-American detainees. Some of them had as little as one-eighth Japanese ancestry.

He was first sent to Manzanar in the California desert, where he remembered blazing heat, barbed wire fences, guard towers and rows of tar-paper-walled pine barracks, one room per family, for the 10,000 residents.

|

| Henry Mittwer (third from left), stands beside his mother, flanked by his two brothers and two neighbors, who are armed with spears and rifles right after Yokohama was devastated in the Great Kanto Earthquake of 1923. (Below) Mittwer with his mother in a photo taken when he was 5. COURTESY OF HENRY MITTWER |

|